What Is GNU Radio: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(→A modular, flowgraph based Approach to Digital Signal Processing: : Make block example list collapsible (and pre-collapsed), because this was frankly overburdening the reader and of no significant content. Showing off is nice – but let's not hurt the reader.) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div style="float:right"> | |||

{{Template:BeginnerTutorials}} | {{Template:BeginnerTutorials}} | ||

</div> | |||

== What is GNU Radio? == | == What is GNU Radio? == | ||

| Line 34: | Line 35: | ||

To understand better, let's look at a common "signal" scenario: Recording voice for transmission using a cellphone. | To understand better, let's look at a common "signal" scenario: Recording voice for transmission using a cellphone. | ||

A person physically speaking creates a sound 'signal' - the signal, in this case, is comprised of waves of varying air pressure being generated by the vocal chords of a human. A time-varying physical quantity, like the air pressure | A person physically speaking creates a sound ''signal'' - the signal, in this case, is comprised of waves of varying air pressure being generated by the vocal chords of a human. A signal is a time-varying physical quantity, like the air pressure. | ||

[[File:sound_vocal.png|sound_vocal.png]] | [[File:sound_vocal.png|sound_vocal.png]] | ||

| Line 42: | Line 43: | ||

[[File:p_to_u.png|p_to_u.png]] | [[File:p_to_u.png|p_to_u.png]] | ||

Now that the signal is electrical, we can work with it. The audio signal, at this point, is analog | Now that the signal is electrical, we can work with it. The audio signal, at this point, is ''analog'' – a computer can't yet deal with it; for computational processing, a signal has to be ''digital'', which means two things: | ||

; It can only be one of a limited number of values. | |||

: The signal can vary over time, but for every instant, it only takes one value – and that value isn't from some "continuum" (like <math>[-1.5;+1.5]</math>, but from some finite set (like <math>\{-1.50, -1.49, \ldots, +1.49, +1.50\}</math>). | |||

; It only exists for a discrete set of points in time | |||

: The signal isn't defined for just any point in time – the points in time are separate, and countable. You can say "this is the first point in time for which the signal takes a specific value, this is the second point in time…". | |||

[[File:cont_to_digital.png|cont_to_digital.png]] | [[File:cont_to_digital.png|cont_to_digital.png]] | ||

This digital signal can thus be represented by a sequence of numbers, called samples. A fixed time interval between samples leads to a signal sampling rate. | This ''digital signal'' can thus be represented by a sequence of numbers, called ''samples''. A fixed time interval between samples leads to a signal ''sampling rate''. | ||

The process of taking a physical quantity (voltage) and converting it to digital samples is done by an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The complementary device, a Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC), takes numbers from a digital computer and converts them to an analog signal. | The process of taking a physical quantity (voltage) and converting it to digital samples is done by an ''Analog-to-Digital Converter'' (ADC). The complementary device, a ''Digital-to-Analog Converter'' (DAC), takes numbers from a digital computer and converts them to an analog signal. | ||

Now that we have a sequence of numbers, our computer can do anything with it. It might, for example, apply digital filters, compress it, recognize speech, or transmit the signal using a digital link. | Now that we have a sequence of numbers, our computer can do anything with it. It might, for example, apply digital filters, compress it, recognize speech, or transmit the signal using a digital link. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 66: | ||

[[File:antenna.png|antenna.png]] | [[File:antenna.png|antenna.png]] | ||

This electrical signal is then on a 'carrier frequency', which is usually several Mega- or even Gigahertz. | This electrical signal is then on a ''carrier frequency'', which is usually several Mega- or even Gigahertz. | ||

Different types of receivers (e.g. Superheterodyne Receiver, Direct Conversion, Low Intermediate Frequency Receivers), which can be acquired commercially as dedicated software radio peripherals, are already available to users (e.g. amateur radio receivers connected to sound cards) or can be obtained when re-purposing cheaply available consumer digital TV receivers (the notorious [https://www.rtl-sdr.com/about-rtl-sdr/ RTL-SDR] project). | Different types of receivers (e.g. Superheterodyne Receiver, Direct Conversion, Low Intermediate Frequency Receivers), which can be acquired commercially as dedicated software radio peripherals, are already available to users (e.g. amateur radio receivers connected to sound cards) or can be obtained when re-purposing cheaply available consumer digital TV receivers (the notorious [https://www.rtl-sdr.com/about-rtl-sdr/ RTL-SDR] project). | ||

| Line 83: | Line 86: | ||

GNU Radio comes with a large set of existing blocks. An index to all of them can be found in [https://wiki.gnuradio.org/index.php/Category:Block_Docs Block Docs]. Just to give you but a small excerpt of what's available in a standard installation, here's some of the most popular block categories and a few of their members: | GNU Radio comes with a large set of existing blocks. An index to all of them can be found in [https://wiki.gnuradio.org/index.php/Category:Block_Docs Block Docs]. Just to give you but a small excerpt of what's available in a standard installation, here's some of the most popular block categories and a few of their members: | ||

* Waveform Generators | * Waveform Generators <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** Constant Source | ** Constant Source | ||

** Noise Source | ** Noise Source | ||

** Signal Source (e.g. Sine, Square, Saw Tooth) | ** Signal Source (e.g. Sine, Square, Saw Tooth) | ||

</div> | |||

* Modulators | * Modulators <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** AM Demod | ** AM Demod | ||

** Continuous Phase Modulation | ** Continuous Phase Modulation | ||

| Line 97: | Line 101: | ||

** WBFM Receive | ** WBFM Receive | ||

** NBFM Receive | ** NBFM Receive | ||

</div> | |||

* Instrumentation (i.e., GUIs) | * Instrumentation (i.e., GUIs) <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** Constellation Sink | ** Constellation Sink | ||

** Frequency Sink | ** Frequency Sink | ||

| Line 106: | Line 111: | ||

** Time Sink | ** Time Sink | ||

** Waterfall Sink | ** Waterfall Sink | ||

</div> | |||

* Math Operators | * Math Operators <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** Abs | ** Abs | ||

** Add | ** Add | ||

| Line 117: | Line 123: | ||

** RMS | ** RMS | ||

** Subtract | ** Subtract | ||

</div> | |||

* Channel Models | * Channel Models <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** Channel Model | ** Channel Model | ||

** Fading Model | ** Fading Model | ||

** Dynamic Channel Model | ** Dynamic Channel Model | ||

** Frequency Selective Fading Model | ** Frequency Selective Fading Model | ||

</div> | |||

* Filters | * Filters <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** Band Pass / Reject Filter | ** Band Pass / Reject Filter | ||

** Low / High Pass Filter | ** Low / High Pass Filter | ||

| Line 133: | Line 141: | ||

** Root Raised Cosine Filter | ** Root Raised Cosine Filter | ||

** FFT Filter | ** FFT Filter | ||

</div> | |||

* Fourier Analysis | * Fourier Analysis <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed"> | ||

** FFT | ** FFT | ||

** Log Power FFT | ** Log Power FFT | ||

| Line 148: | Line 157: | ||

** PN Correlator | ** PN Correlator | ||

** Polyphase Clock Sync | ** Polyphase Clock Sync | ||

</div> | |||

Using these blocks, many standard tasks, like normalizing signals, synchronization, measurements, and visualization can be done by just connecting the appropriate block to your signal processing flow graph. | Using these blocks, many standard tasks, like normalizing signals, synchronization, measurements, and visualization can be done by just connecting the appropriate block to your signal processing flow graph. | ||

| Line 153: | Line 163: | ||

Also, you can write your own blocks, that either combine existing blocks with some intelligence to provide new functionality together with some logic, or you can develop your own block that operates on the input data and outputs data. | Also, you can write your own blocks, that either combine existing blocks with some intelligence to provide new functionality together with some logic, or you can develop your own block that operates on the input data and outputs data. | ||

Thus, GNU Radio is mainly a framework for the development of signal processing blocks and their interaction. It comes with an extensive standard library of blocks, and there are a lot of systems available that a developer might build upon. However, GNU Radio itself is not | Thus, GNU Radio is mainly a framework for the development of signal processing blocks and their interaction. It comes with an extensive standard library of blocks, and there are a lot of systems available that a developer might build upon. However, GNU Radio itself is not software that is ready to do something specific -- it's the user's job to build something useful out of it, though it already comes with a lot of useful working examples. Think of it as a set of building blocks. | ||

Latest revision as of 13:17, 4 December 2022

| Beginner Tutorials

Introducing GNU Radio Flowgraph Fundamentals

Creating and Modifying Python Blocks DSP Blocks

SDR Hardware |

What is GNU Radio?

GNU Radio is a free & open-source software development toolkit that provides signal processing blocks to implement software radios. It can be used with readily-available low-cost external RF hardware to create software-defined radios, or without hardware in a simulation-like environment. It is widely used in research, industry, academia, government, and hobbyist environments to support both wireless communications research and real-world radio systems.

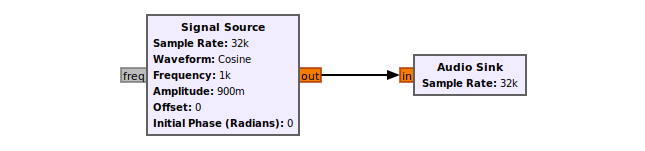

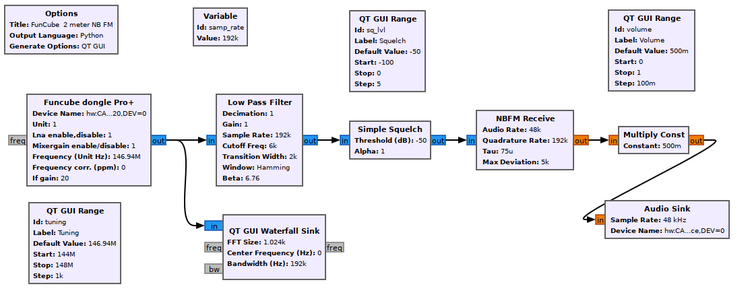

Below shows an example flowgraph within the GNU Radio Companion visual editor:

GNU Radio is a framework that enables users to design, simulate, and deploy highly capable real-world radio systems. It is a highly modular, "flowgraph"-oriented framework that comes with a comprehensive library of processing blocks that can be readily combined to make complex signal processing applications. GNU Radio has been used for a huge array of real-world radio applications, including audio processing, mobile communications, tracking satellites, radar systems, GSM networks, Digital Radio Mondiale, and much more - all in computer software. It is, by itself, not a solution to talk to any specific hardware. Nor does it provide out-of-the-box applications for specific radio communications standards (e.g., 802.11, ZigBee, LTE, etc.,), but it can be (and has been) used to develop implementations of basically any band-limited communication standard.

Why would I want GNU Radio?

Formerly, when developing radio communication devices, the engineer had to develop a specific circuit for detection of a specific signal class, design a specific integrated circuit that would be able to decode or encode that particular transmission and debug these using costly equipment.

Software-Defined Radio (SDR) takes the analog signal processing and moves it, as far as physically and economically feasible, to processing the radio signal on a computer using algorithms in software.

You can, of course, use your computer-connected radio device in a program you write from scratch, concatenating algorithms as you need them and moving data in and out yourself. But this quickly becomes cumbersome: Why are you re-implementing a standard filter? Why do you have to care how data moves between different processing blocks? Wouldn't it be better to use highly optimized and peer-reviewed implementations rather than writing things yourself? And how do you get your program to scale well on a multi-core architectures but also run well on an embedded device consuming but a few watts of power? Do you really want to write all the GUIs yourself?

Enter GNU Radio: A framework dedicated to writing signal processing applications for commodity computers. GNU Radio wraps functionality in easy-to-use reusable blocks, offers excellent scalability, provides an extensive library of standard algorithms, and is heavily optimized for a large variety of common platforms. It also comes with a large set of examples to get you started.

The remainder of this page provides a brief intro to DSP, feel free to skip to the next tutorial if you are already familiar with DSP.

Digital Signal Processing

As a software framework, GNU Radio works on digitized signals to generate communication functionality using general-purpose computers.

A little signal theory

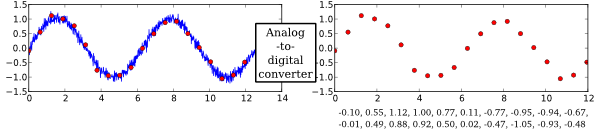

Doing signal processing in software requires the signal to be digital. But what is a digital signal?

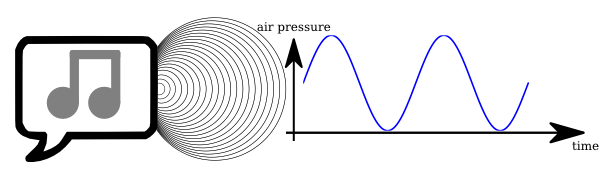

To understand better, let's look at a common "signal" scenario: Recording voice for transmission using a cellphone.

A person physically speaking creates a sound signal - the signal, in this case, is comprised of waves of varying air pressure being generated by the vocal chords of a human. A signal is a time-varying physical quantity, like the air pressure.

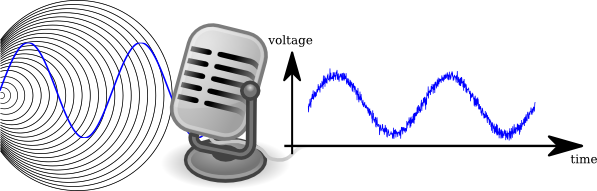

When the waves reach the microphone, it converts the varying pressure into an electrical signal, a variable voltage:

Now that the signal is electrical, we can work with it. The audio signal, at this point, is analog – a computer can't yet deal with it; for computational processing, a signal has to be digital, which means two things:

- It can only be one of a limited number of values.

- The signal can vary over time, but for every instant, it only takes one value – and that value isn't from some "continuum" (like , but from some finite set (like ).

- It only exists for a discrete set of points in time

- The signal isn't defined for just any point in time – the points in time are separate, and countable. You can say "this is the first point in time for which the signal takes a specific value, this is the second point in time…".

This digital signal can thus be represented by a sequence of numbers, called samples. A fixed time interval between samples leads to a signal sampling rate.

The process of taking a physical quantity (voltage) and converting it to digital samples is done by an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The complementary device, a Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC), takes numbers from a digital computer and converts them to an analog signal.

Now that we have a sequence of numbers, our computer can do anything with it. It might, for example, apply digital filters, compress it, recognize speech, or transmit the signal using a digital link.

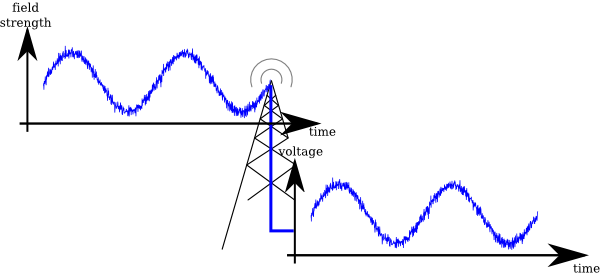

Applying Digital Signal Processing to Radio Transmissions

The same principles as for sounds can be applied to radio waves:

A signal, here electromagnetic waves, can be converted into a varying voltage using an antenna.

This electrical signal is then on a carrier frequency, which is usually several Mega- or even Gigahertz.

Different types of receivers (e.g. Superheterodyne Receiver, Direct Conversion, Low Intermediate Frequency Receivers), which can be acquired commercially as dedicated software radio peripherals, are already available to users (e.g. amateur radio receivers connected to sound cards) or can be obtained when re-purposing cheaply available consumer digital TV receivers (the notorious RTL-SDR project).

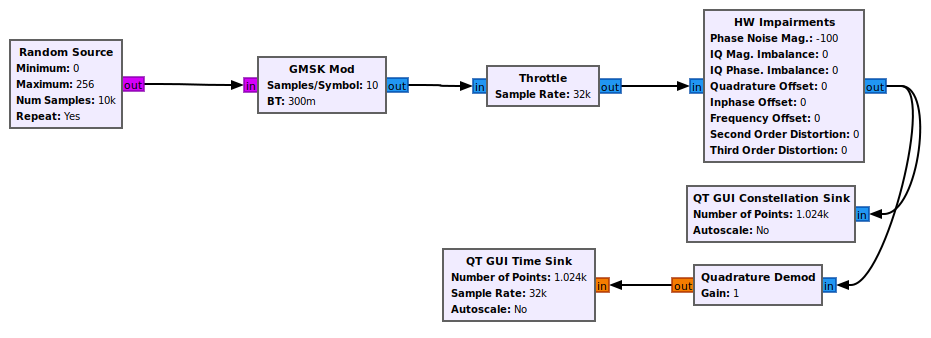

A modular, flowgraph based Approach to Digital Signal Processing

To process digital signals, it is straight-forward to think of the individual processing stages (filtering, correction, analysis, detection...) as processing blocks, which can be connected using simple flow-indicating arrows:

When building a signal processing application, one will build up a complete graph of blocks. Such a graph is called flowgraph in GNU Radio.

GNU Radio is a framework to develop these processing blocks and create flowgraphs, which comprise radio processing applications.

As a GNU Radio user, you can combine existing blocks into a high-level flowgraph that does something as complex as receiving digitally modulated signals and GNU Radio will automatically move the signal data between these and cause processing of the data when it is ready for processing.

GNU Radio comes with a large set of existing blocks. An index to all of them can be found in Block Docs. Just to give you but a small excerpt of what's available in a standard installation, here's some of the most popular block categories and a few of their members:

- Waveform Generators

- Constant Source

- Noise Source

- Signal Source (e.g. Sine, Square, Saw Tooth)

- Modulators

- AM Demod

- Continuous Phase Modulation

- PSK Mod / Demod

- GFSK Mod / Demod

- GMSK Mod / Demod

- QAM Mod / Demod

- WBFM Receive

- NBFM Receive

- Instrumentation (i.e., GUIs)

- Constellation Sink

- Frequency Sink

- Histogram Sink

- Number Sink

- Time Raster Sink

- Time Sink

- Waterfall Sink

- Math Operators

- Abs

- Add

- Complex Conjugate

- Divide

- Integrate

- Log10

- Multiply

- RMS

- Subtract

- Channel Models

- Channel Model

- Fading Model

- Dynamic Channel Model

- Frequency Selective Fading Model

- Filters

- Band Pass / Reject Filter

- Low / High Pass Filter

- IIR Filter

- Generic Filterbank

- Hilbert

- Decimating FIR Filter

- Root Raised Cosine Filter

- FFT Filter

- Fourier Analysis

- FFT

- Log Power FFT

- Goertzel (Resamplers)

- Fractional Resampler

- Polyphase Arbitrary Resampler

- Rational Resampler (Synchronizers)

- Clock Recovery MM

- Correlate and Sync

- Costas Loop

- FLL Band-Edge

- PLL Freq Det

- PN Correlator

- Polyphase Clock Sync

Using these blocks, many standard tasks, like normalizing signals, synchronization, measurements, and visualization can be done by just connecting the appropriate block to your signal processing flow graph.

Also, you can write your own blocks, that either combine existing blocks with some intelligence to provide new functionality together with some logic, or you can develop your own block that operates on the input data and outputs data.

Thus, GNU Radio is mainly a framework for the development of signal processing blocks and their interaction. It comes with an extensive standard library of blocks, and there are a lot of systems available that a developer might build upon. However, GNU Radio itself is not software that is ready to do something specific -- it's the user's job to build something useful out of it, though it already comes with a lot of useful working examples. Think of it as a set of building blocks.

![{\displaystyle [-1.5;+1.5]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/682d2b8a6155332aaa90990b3d9c6c9a50b45192)